“Spacecraft dust” from defunct satellites burning up in Earth’s atmosphere could weaken our planet’s magnetic field, a controversial new paper suggests.

In the worst-case scenario, the unchecked expansion of commercial satellite “megaconstellations” orbiting Earth, such as SpaceX’s Starlink network, may generate enough magnetic dust to cut our planet’s protective shield in half, potentially leading to satellite disasters and “atmospheric stripping,” the paper’s author told Live Science.

But is this outcome really likely? Other researchers are skeptical of the paper’s claims, though they all agree on one thing: there’s an urgent need to quantify the scale of the problem.

Private satellites currently in orbit are a rapidly growing headache for astronomers due to their tendency to photobomb cosmic images and interfere with radio telescopes, as well as the increased risk of collisions with other spacecraft. But the real threat they pose may be what happens to them when they die.

When spacecraft end their missions, most are deorbited and burned up in Earth’s atmosphere to minimize the amount of space junk circling our planet. However, as they fall apart in flames, the dying spacecraft litter our upper atmosphere with vaporized metal pollution.

Related: Sci-fi inspired tractor beams are real, and could solve a major space junk problem

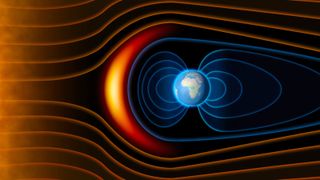

In the new theoretical paper, uploaded to the pre-print database arXiv in December 2023 but not yet peer-reviewed, Sierra Solter-Hunt, a doctoral candidate at the University of Iceland, proposed that this atmospheric spacecraft dust may compromise the magnetosphere — the part of Earth’s magnetic field that extends into space and protects the atmosphere from solar radiation.

Solter-Hunt is concerned that if satellite megaconstellations evolve as planned, the amount of dust they release may create a magnetic shield that could limit the magnetosphere’s reach.

“I was shocked at everything that I found and that nobody has been studying this,” Solter-Hunt told Live Science. “I think it’s really, really alarming.”

Accumulating dust

We currently have no way of monitoring the amount of spacecraft dust in the atmosphere, but based on the amount of space junk that has already burned up on reentry, we could have increased the amount of metallic particulate in the skies by a million-fold since the start of the space age, Solter-Hunt said.

And Solter-Hunt estimated between 500,000 and 1 million private satellites could orbit our planet in the coming decades. When all these satellites eventually fall to Earth it could dramatically increase the amount of spacecraft dust in the atmosphere to billions of times its current level, she said.

Related: How many satellites orbit Earth?

It is currently unclear where all of this spacecraft dust will eventually end up but Solter-Hunt thinks that it will probably settle in the upper part of the ionosphere — a region of the atmosphere between 50 and 400 miles (80 and 644 kilometers) above the surface. “And it could just stay there forever,” she added.

Magnetic shielding

If all these proposed satellites go up in flames, the resulting spacecraft dust could create a “perfect conductive net around our planet” that could be capable of carrying an electric charge, Solter-Hunt said. If this happened, the magnetosphere, which normally extends thousands of miles into space, would be “distorted to stay under the conducting material,” essentially limiting its reach to the upper ionosphere, she added.

A reduced magnetic field could expose satellites to high levels of radiation and solar storms, which could knock them out of the sky, Solter-Hunt said. “It’s a real Catch-22 for satellite companies,” she added. “They could be weakening the magnetosphere with what they’re doing, which in turn puts themselves at risk.”

But even if the magnetosphere doesn’t shrink, the increased levels of spacecraft dust could still make it harder for rockets to launch new satellites and other spacecraft into space, Solter-Hunt said. This is because the magnetic particles could interfere with onboard electronics, she added.

Worst-case scenario

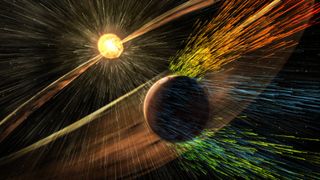

In Solter-Hunt’s worst-case scenario, increased levels of radiation bombarding the upper ionosphere could begin to blow away the outer edges of our atmosphere — a phenomenon known as “atmospheric stripping,” which has naturally occurred on planets like Mars and Mercury.

But this would be the “most extreme case” and may take centuries, if not millennia, to occur, she added.

Related: NASA and Japan to launch world’s 1st wooden satellite as soon as 2024. Why?

But even if the atmosphere remains intact, spacecraft dust could still damage it.

Past studies have suggested that some of this pollution, particularly alumina (aluminum oxide), could deplete atmospheric ozone, potentially increasing the size of the ozone holes above Earth’s polar regions.

The magnetosphere is also undergoing some natural weakening as the Earth’s core grows and solidifies, and nobody knows if spacecraft dust could accelerate this process or not.

‘Important first step’

Some researchers praise the new paper for highlighting hidden potential issues of spacecraft dust.

“This work is a really important first step” and highlights the “terrifying” amount of spacecraft dust that could be deposited in the atmosphere, Samantha Lawler, an astronomer at the University of Regina in Canada, told Live Science in an email. “The consequences [of this pollution] could also be on a totally different scale than we’re used to thinking about,” she added.

Related: SpaceX rockets keep tearing blood-red ‘atmospheric holes’ in the sky, and scientists are concerned

However, other experts think that the scenarios laid out by Solter-Hunt are too speculative or based on flawed assumptions.

“Even at the densities [of spacecraft dust] discussed, a continuous conductive shell like a true magnetic shield is unlikely,” John Tarduno, a planetary scientist and magnetosphere expert at the University of Rochester in New York, told Live Science in an email. Some of the assumptions in the paper are also “too simple and unlikely to be correct,” he added.

In particular, no one has modeled how spacecraft dust will settle in the atmosphere, how long it will last or how conductive it will be, meaning there is no proof that magnetic shielding is possible, José Ferreira, a doctoral candidate at the University of Southern California who is also studying space dust pollution, told Live Science in an email.

The number of potential satellites orbiting Earth in the future also “seems exaggerated,” as many touted satellite launches never occur, Fionagh Thompson, a research fellow at Durham University in England who specializes in space ethics, told Live Science in an email.

The paper is an “interesting thought experiment,” Thompson added. But without clearly outlining exactly how spacecraft dust will cause these problems, “it shouldn’t be passed off as ‘this is what is going to happen’,” she said.

Solter-Hunt understands the researchers’ criticism. However, due to the imminent rise in satellite launches, she wanted to share her theories with the scientific community. “I could be totally wrong,” she said. “But I put it there so everyone can see it and talk about it.”

And, despite their reservations about this paper, the experts all agree that more research is urgently needed to study the possible effects of metal pollution in the atmosphere.

“This is not an issue to be ignored,” Thompson said. “There is a need to step back and view this [space junk pollution] as a completely new phenomenon.”

“There’s a desperate need to study this as fast as possible,” Lawler added. “Honestly, I don’t think anyone knows what could happen.”