When Jews Were Saved: Celebrating Personal and Communal Salvations throughout History

Sitting in Yad Vashem, Israel’s Holocaust Museum, is a scroll unlike any other. Its name is Megillat Hitler, and instead of telling the story of Esther saving the Jewish people from annihilation, it relates the events of the Holocaust, from Hitler’s rise to power, to the occupation of Europe, and the murder of Jews and stealing of their property1. The last three chapters retells how the Jews of North Africa were saved and liberated by the allies. But the author, Prosper Hassine, a scribe and teacher in Casablanca, was careful to note this story is not meant to be read joyfully. While the Jews of North Africa were saved, they had lost millions of their Jewish brothers and sisters. He writes that the Megillah should be read with a serious demeanor while remembering the victims.

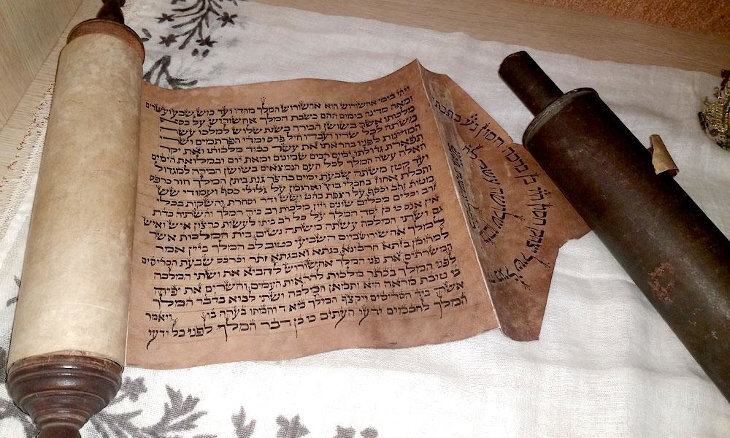

Megillat Hitler, rolled together with a Megillat Esther, Casablanca, Morocco, 1944, Yad Vashem Artifact Collection, Donated by Alberto Corcos, Herziliyah, Israel

The idea of writing one’s own Megillah, scroll in Hebrew, for a personal or community salvation from murderous antisemites is not new. In fact, there’s a name for it—Second Purim, and it dates back to the middle ages, when blood libels and attempts to wipe out whole Jewish communities were very common2. Rabbi Avraham Danzig, the famed Lithuanian Rabbi of the 19th century in his halachic work, Hayei Adam, wrote: “Anyone to whom a miracle happened, or all the residents of a city, can ordain by mutual agreement or by censure upon themselves and all who come after them, to make that day a Purim. And it seems to me that the festive meal that they make to celebrate the miracle is a seudat mitzvah, a festive meal.” (Sefer Chayei Adam, Hilkhot Megillah 155, ¶41, on Orach Chayim 686). In a footnote he includes the story of his own personal “Purim” miracle when a deadly gunpowder explosion in Vilna destroyed his house and property, but spared his life.

People perform many of the traditional Purim customs, like writing a special megillah to retell the events that led to their salvation, composing a unique poem or prayer, or eating a festive meal on the day. They might give charity to the poor, take the day off work, or exchange mishloach manot, gifts of food with friends.3

Second Purims were celebrated by Jews around the world in many different communities. For example, in 1236, there was a fight in Narbonne, France between a Jewish traveler and a Christian fisherman4. In response, Christian residents rioted in the Jewish quarter, and violence against the Jews was imminent. Fortunately, a local viscount, Don Aymeric, intervened on behalf of the Jews and with his troops brought peace and order back to the city5. Rabbi Meir ben Isaac, an eyewitness to the event (who had the contents of his library stolen by the Christian mob and later returned to him) wrote a megillah commemorating the event.6

In Gumeldjina, part of the Ottoman Empire in 1786, a group of 5,000 mountain bandits attacked the city, and although the governor managed to drive off the invaders, the Jews were accused of conspiring with them.7 At great lengths, the community proved that they were innocent, and saved themselves from death, banishment, or wrongful imprisonment.

In 1793 Libya, a new king named Ali Burghul Pasha Cezayrli usurped the throne8. He established a reign of terror against the Jews until 1795 when he was finally deposed. The Jewish community established a Second Purim to celebrate his downfall and their freedom from tyranny.

In Rhodes in the 1840s, the Greeks resented having to compete against Jews for their livelihood in the sponge trade, so they fabricated a blood libel against them. They claimed that a Christian child who had disappeared had been killed by the Jews. Later, the child was found alive and well on a different Greek Island and the Sultan, Abd al-Majid, sacked the governor, and issued a ruling saying that the accusations were false. The date of the sultan’s ruling was on Purim itself, so the Jews of Rhodes celebrated a double holiday that day.9

The Megillah of Esther from Rhodes, dated 1864, displayed at Rhodes Jewish Museum

The Megillah of Esther from Rhodes, dated 1864, displayed at Rhodes Jewish Museum

People also celebrate Second Purim for a personal salvation. In 1731, David Brandeis of Bohemia had a shop where he sold jam. A girl from a Christian family purchased a jar of jam. Her whole family fell sick and a few days later her father died. The city closed David’s store and arrested him, his wife, and son for selling poisonous food to a Christian. Later, the authorities realized that the man had actually died from tuberculosis and David and his family were released and exonerated. David wrote a scroll about these events, which he asked his family to read every year on the tenth of Adar, and he also asked that his family enjoy a festive meal on the same day. Brandeis’ descendants were still celebrating Purim Povidl or Jam Purim, well into the nineteenth century.10

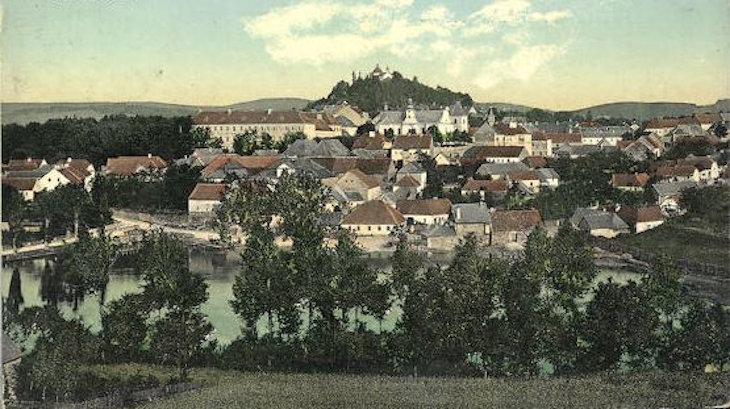

Jungbunzlau, Bohemia where David Brandeis and his family evaded certain death in 1731

Jungbunzlau, Bohemia where David Brandeis and his family evaded certain death in 1731

My family also has a personal story of survival. My great-grandfather was taken to Dachau on Kristallnacht, but was miraculously let out a few weeks later. He left with his family, including my grandmother, on one of the very last boats taking Jews out of Germany. My grandmother often told us that a German-owned boat and the American-owned boat she was on left for America at the same time. The German-owned boat was called back because the Nazis had changed their minds and decided to send the Jews to a death camp. She had a friend on the German-owned boat and never heard from her again.

Even though my family didn’t write down our story, and we don’t celebrate with a festive meal or shalach manot, it’s something that we talk about often. If it wasn’t for a whole chain of miracles my family wouldn’t be here today. I like to think of it as my personal Purim.

If you’re a Jew alive today, chances are there’s a miraculous story of survival in your family history. I’ve heard from a Persian Jew who escaped from Iran on a donkey, and a French Jew whose grandfather escaped the Nazis by hiding in a truck fill of hay. If you’re grandparents are still alive, ask them for their story of survival, and celebrate the miracle that you are here today.

- “’Megillat Hitler’ Rolled Together with a Megillat Esther (Esther Scroll).” Yad Vashem. The World Holocaust Remembrance Center, www.yadvashem.org/artifacts/featured/megilat-esther.html. Accessed 4 Mar. 2024.

- OU Staff. “When is Purim Observed.” Orthodox Union. 29, June 2006. https://www.ou.org/holidays/when_is_purim_observed/. Accessed 4 Mar. 2024.

- OU Staff. “When is Purim Observed.” Orthodox Union. 29, June 2006. https://www.ou.org/holidays/when_is_purim_observed/. Accessed 4 Mar. 2024.

- Caputo, Nina. Regional history, Jewish memory: the Purim of Narbonne. Jew History 22, 97–114 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10835-007-9048-1

- Ibid

- Deutsch, Gotthard; Franco, M.; Malter, Henry (2011). “Purims, Special”. Jewish Encyclopedia. Accessed 4 Mar. 2024.

- Domnitch, Larry. “Special Purims”. myjewishlearning.com. https://www.myjewishlearning.com/article/special-purims/#:~:text=Pronounced%3A%20PUR%2Dim%2C%20the,is%20in%20itself%20a%20miracle. Accessed 4 Mar. 2024.

- “Second Purim.” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, Wikimedia Foundation. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Second_Purim#cite_note-FOOTNOTEStewart2006225-9. Accessed 4 Mar. 2024.

- Deutsch, Gotthard; Franco, M.; Malter, Henry (2011). “Purims, Special”. Jewish Encyclopedia. Accessed 4 Mar. 2024.

- Maimon, Debbie. “Purim Miracles Across the Centuries.” 1, Mar. 2023. Yated Ne’eman. https://yated.com/purim-miracles-across-the-centuries/. Accessed 4 Mar. 2024.